- Home

- David Kinney

The Dylanologists Page 2

The Dylanologists Read online

Page 2

“Honey,” the woman told her, “it’s about time somebody did something nice for my son in Hibbing.”

Dylan was an eccentric and sensitive kid. Perhaps he wouldn’t have fit anywhere, but growing up, he surely didn’t fit in Hibbing. Later on, after he became famous, writers and critics used to wonder: How did a cultural giant as smart and original as Dylan come from a nowhere sort of place like this?

Hibbing sits in the center of an eighty-mile constellation of settlements that were founded atop a narrow band of low hills called the Mesabi Range. Prospectors began mining iron there in 1890, and soon it become clear they had tapped into one of the richest veins in the world. Within two decades the once-isolated region of forest and bog had sixty-five thousand inhabitants and an array of nationalities: Scandinavian, Finnish, Bohemian, Italian, Polish, Russian, Greek. With miners came hucksters and gamblers and prostitutes and saloons by the dozens. But tax revenues boomed, and the new settlements did not remain bawdy frontier camps for long. Hibbing in particular aspired to greatness, and in short order it touted a fine school, a Carnegie library, a courthouse, a three-story town hall, a hotel, a racetrack, and a zoo with lions and buffalo. What the mines gave, they soon took away. Turned out, ore lay beneath Hibbing’s foundations, and the townspeople had barely settled in when the decision was made to move almost two miles south. Starting in 1918, some two hundred buildings were hoisted onto wheels and inched off the mother lode. A new town hall went up with a clock tower. Howard Street came alive with national chain department stores, a theater, and a plush hotel. North of Hibbing, the strip-mined canyon grew until it sprawled as far as the eye could see. From the ground, it’s a four-mile moonscape. On satellite maps it looks like a spill, something pouring out of the town’s borders. Mining spoils now encircle the city in towering red-earth ridges.

Bob was born in Duluth, an hour and a half’s drive southeast, on May 24, 1941. When he was five, his father, Abe, was struck with polio and housebound for six months. In 1947, having lost his job as a Standard Oil manager, he moved Beatty, Bob, and his second son, David, then one, to Hibbing. They wanted to be closer to their extended families. The Zimmermans were middle-class and Jewish in a town that was predominantly working-class and Christian. Abe was president of the B’nai B’rith lodge and Beatty of the local Hadassah chapter. After he recovered, Abe worked at the appliance business with his brothers, and Beatty worked at a downtown department store, Feldman’s. She was the sort of saleswoman who would call her customers when a new dress appeared that she thought they’d like. It’s perfect for you, come check it out. The Zimmermans did well enough that Beatty had a fur in her closet, and as a teenager Bob had a convertible and his own motorcycle.

Like a lot of kids growing up in the 1950s, Bob fell in love with music through a new lifeline to the world: the transistor radio. In Hibbing, polka ruled. Accordions filled the front window of the town’s music store. But over the airwaves at night, Bob could hear early rock, rhythm and blues, and country on radio stations out of Little Rock and Shreveport, Louisiana. He listened to Elvis, Buddy Holly, Hank Williams, Chuck Berry, Little Richard. Banging away on the guitar and the family piano, he learned how to play what he heard, and then launched a succession of rock bands. Some of Bob’s gigs were at Hibbing High School, a granite-and-limestone colossus that cost nearly $4 million to construct in 1920–22. The hallways were finished in intricate, hand-painted molding and decorated with oil paintings. The doorknobs were brass. The gemstone of the school was an auditorium modeled on New York’s Capitol Theater. It seated eighteen hundred in red velvet seats and boasted a pipe organ and a grand piano, an ornate proscenium, and crystal chandeliers from Europe. Playing on a stage this majestic could plant ostentatious ideas in a teenager’s head.

Over the years, pilgrims to Hibbing were surprised that Dylan was not hailed as a local hero. A visitor could come and go and never realize the connection. Wear a Dylan T-shirt in Hibbing and you were liable to get an earful from the locals about how much they wanted to pummel that no-good weirdo when they were growing up. After Dylan landed his record deal—only two years out of high school—he fabricated a new biography for himself. He told interviewers he’d run away from home repeatedly. He’d lived in Gallup, New Mexico, and Marysville, Texas, and Sioux Falls, South Dakota. He’d been a “roustabout” for carnivals. In Hibbing, people couldn’t understand why Dylan went to such lengths to deny growing up middle-class in their respectable city.

Decades later, he was still less popular locally than Kevin McHale, the basketball star who won three NBA championships with the Boston Celtics. McHale kept a hunting lodge north of town and always spoke highly of the place. “It’s rough up here,” said David Vidmar, a mining industry consultant whose aunt bought the Zimmerman house after Dylan’s father died. “You could probably understand why a lot of people didn’t care for him. Myself included. I hunt and fish. Poetry? Sorry. People worked in the mines. They’re not listening to poems.” When Aaron Brown was growing up in Hibbing in the 1980s and 1990s, he had no idea that Dylan was any more important than any other rock star on the radio. “The fact that Dylan was a big deal? We got sex ed before we got that,” said Brown, a columnist for the Hibbing Daily Tribune. “If we had a mayor’s election between Kevin McHale and Bob Dylan, Kevin McHale would win with eighty percent of the vote.”

Eventually, Dylan spoke warmly about his hometown. “I am proud to be from Hibbing,” he said when he was thirty-seven and a father himself. He saw something mystical in the North Country. “You can have some amazing hallucinogenic experiences doing nothing but looking out your window.”

What his high school girlfriend, Echo Helstrom, remembered was being bullied for something like twelve years. She spent a lot of time being angry at the world. She had to laugh when she thought about the glamorous photo of her up on the sign at Zimmy’s. There she was, looking down at all the people who were mean to her growing up. After school, after moving to California and finding a job in the film business, Helstrom never considered going back. Yet, weirdly, Hibbing still had a hold on her. “My heart just can’t leave it and be done with it. It’s still home to me.” Although they did not stay in touch, she suspected Dylan felt the same.

Still, she couldn’t imagine Dylan coming to Hibbing for some grand homecoming, where he could be feted as a hometown hero. Bob Hocking’s grand fantasy was that Dylan would visit for a farewell concert at the high school theater, but it’s safe to say something like that is not going to happen. It’s a crazy idea—as crazy as thinking that Dylan would drive over to Zimmy’s one day, stroll in the front door with a smile, and order up the “Slow Train” veggie pizza ($8.49, gluten free!).

But that afternoon in 2004 after Myrtle’s funeral, Hocking could not help himself. He had to hope. Maybe, maybe, maybe. Maybe.

Then he saw it: a news truck parked right next to the restaurant. He saw it, and he knew.

No way Dylan would run that gauntlet. The cameramen were inside eating lunch, but Hocking didn’t ask them to move their van to a less conspicuous spot. Customers were customers. Instead he hung around until one, watching and waiting, then gave up and went back to the office. He shrugged it off. If it wasn’t meant to be, it wasn’t meant to be, and anyway, sometimes the fantasy was better than the reality.

Later, word came back that Dylan had stopped in on his uncle before departing. There was some excitement at Zimmy’s when Dylan’s nephews walked in for lunch and hung around for a couple of hours. Linda, just as she had done with Beatty a decade earlier, chatted and handed over a bunch of Zimmy’s swag. When she offered them a shirt to give to their uncle, they laughed. You should know something about Bob, they explained to her. He doesn’t wear shirts bearing his own likeness.

Six years on, Dylan turned up again, and this time the Hockings had no clue he might appear. He arrived with a woman nobody recognized. They looked at the school and the family movie theater and some other sites.

But, again, Zimmy’s was not on the itinerary. On the outskirts of town, Dylan and the woman stopped into a coffee shop. A friend of Bob Hocking’s happened to be there. “I know who you are,” he told the singer. “You’re that Bob Dylan guy.” He left with an autograph on a napkin.

By the time word got back to Hocking, Dylan was gone—just a rumor.

3

At least the Hockings could count on the pilgrims to show. On a warm spring night, one day after Dylan turned seventy, an out-of-town couple ducked into Zimmy’s and took a couple of stools at the bar, where they ordered hoppy beers and watched for fellow travelers. All over the world, fans were celebrating with tribute shows and symposiums. The press and the blogosphere were filled with plaudits from writers who grew up on Dylan. Hibbing was hosting its annual Dylan Days arts festival, a tradition that began with informal birthday bashes the Hockings started at Zimmy’s in 1991. The Dylan freaks were descending on the town in waves for a long weekend—by motorcycle from Ontario, by car from Fargo and Minneapolis, by jet from Australia and the Netherlands. They wanted to see the sights, breathe the North Country air, and raise their glasses to their hero, the Bard of Hibbing, Minnesota. He had been invited.

The couple, Nina Goss and Charlie Haeussler, newlyweds at age fifty, had flown in that day from New York. They checked in to a hotel on Howard and left on foot to make the rounds to some of the key Dylan landmarks before retiring to the bar for the duration of the evening. This was their second visit to Hibbing, and it felt a little like a homecoming. Linda Stroback walked by their bar stools and, recognizing them, swept in for hugs. The restaurateur was hoarse and overbooked, and the festivities were only beginning. But Linda looked ebullient as ever, and so did Nina and Charlie.

Ever since their first trip, they’d told every Dylan fanatic who would listen, “You must go to Hibbing.” The last time, Charlie had welled up at the sight of the piano Bob had banged away on at the high school. Nina had spent hours at Zimmy’s talking about William Carlos Williams and Walt Whitman with Bob’s charismatic English teacher.

Nina left town convinced of one thing: It was wrong to think of this place as too small, too parochial, to have spawned a genius of Dylan’s stature. She found the town to be a time capsule, a little community that encompassed the whole sweeping story of American growth. Immigrants drawn west, finding jobs and fresh starts, flourishing and assimilating. How different was that from the story of her big city back home? Hibbing had labor riots as the miners went to war with the big steel companies back east. It had a mayor whose advocacy for the workers and antagonism toward big business won him comparisons to the great populist Huey Long. It was the quintessential melting pot, and it had a vibrant Jewish community. It was more confining than a big city, of course, but more bustling than you’d expect from a little flyspeck up in the middle of nowhere. So yes, sure, Dylan had fled Hibbing, but by Nina’s way of thinking, it was only “the very first of countless places” he had spurned. He ran away from New York City, too. Only a fool would think he didn’t take a dose of Hibbing’s history with him in his veins. Now that she knew the place, she heard it in Dylan’s songs.

She and Charlie had returned to Hibbing because if you’re a Dylan maniac, then being in the places where he became what he became is thrilling, if irrational. You could see the coffee shop where he ate cherry pie with his girlfriend. You could meet the guy who played drums in his high school band. And what hard-core fanatic wouldn’t want to drink beers surrounded by a hundred photographs of the man? “That,” Nina said, “is my idea of heaven.”

She was an overachiever among the pilgrims, a recent convert who proselytized with zeal. Nina, who has a doctorate in literature and taught English at the college level, speaks and writes about Dylan in thickly layered sentences that unfurl like frantic attempts to grasp the truth. In 2005, having never listened to the singer before, she read his engaging and unconventional memoir, Chronicles: Volume One. She fell, and hard. “If anybody can say a book changed their life,” she allowed, “I would join that rarefied list of eccentrics.” It did not escape her notice that in 1961, she and Bob Dylan both shivered through their first New York winters. He was nineteen and on the make. She was a newborn. A few weeks after reading the book, she found herself in the eighth row of a theater in Manhattan thinking she had gone entirely crazy. Why was she falling in love with this old man’s music? She was strangely nervous, sitting there that night. Nina is a wisp of a woman with brown hair that bunches in tight coils. When she is engaged, her eyes don’t focus so much as penetrate. You can just about see the synapses firing. That night, she was no passive audience member. She concentrated, she worked.

Dylan came on stage. He had the inscrutable look and the piercing blue eyes that have intimidated armies of admirers, and he swept away the woman in row eight. She told me later that she was “completely and utterly unprepared for what an extraordinarily expressive and communicative presence he was onstage.” She had been a lifelong opera aficionado, but Dylan killed her interest in it. It felt artificial, mannered, shallow. She had seen the best, but “they’re trained animals compared to what Dylan does,” she said. “My mother would probably put her head in the oven to hear me say that.”

In the handful of years after her discovery, Nina’s life began to revolve around Dylan. She loitered on the Internet forums. She went to an adult-education class, dozens of shows, and a meet-up group, where she met Charlie. It made sense that she would find love in a Dylan circle: It was inconceivable for her to be with a man who was not equally consumed. She felt a burning need to write about Dylan, so she prepared a paper for a conference, and edited a book of academic writing, and started a thoughtful, earnest blog. She launched a journal, recruiting fresh voices to write for it in hopes that they would bring something new to the study of his music. She showed up at just about anything Dylan-related. When he played in New York, she waited in the long lines. When Fordham Law School hosted a day-long symposium about Dylan and the law, she sat and listened to every presentation.

And now this week she was in Hibbing with Charlie. They tucked into the cherry pie à la mode (Bob’s favorite, honest) and Beatty’s banana chocolate-chip loaf bread (“a wonderful recipe and to make it is so easy, dear,” Mom said). They went to the basement cafeteria at the Memorial Building Arena for a rock ’n’ roll hop headlined by one of the guys who played guitar with Bob in high school. They rode on a tour bus to see the synagogue and the hotel where Bob had his bar mitzvah, and the lodgings of the rabbi who prepared him for it, and the shop where his father, Abe, worked, and the railroad crossing where Bob and his motorcycle were nearly jackhammered by a passing locomotive. They saw the old Zimmerman place. They visited Echo’s house, where people stood out front and snapped photos of the remains of the tree swing, so evocative of teen romance.

Nina knew that nothing about these Dylan-themed adventures made her particularly unique. “There are all kinds of people who would lay claim to being the greatest Dylan fan in the world,” she said. “I would say I am. But the world is full of us.”

The world was also full of people who looked at Dylan and were puzzled. They might have heard they should appreciate him as they would Shakespeare, Homer, Mozart. They might have heard that Dylan was a towering figure who changed the course of music, influenced everyone who followed, revolutionized songwriting. But they watched and they listened and they didn’t understand. Dylan appeared on television and he seemed entirely out of place, all peculiar mannerisms and gnomic pronouncements. Accepting a lifetime achievement award at the Grammys in 1991, he looked at the camera and said, “My daddy, he didn’t leave me much, you know he was a very simple man. But what he did tell me was this. He did say, ‘Son,’ he said—” He paused for a few interminable seconds, grinning and playing with a funny hat. “He said, ‘You know, it’s possible to become so defiled in this world that your own father and mother will abandon you, and if that happens, God will always believe i

n your ability to mend your ways.’ ” (It took some digging for Dylanologists to discover that he’d borrowed that from rabbinical commentary on Psalm 27.) Twenty years later, when he returned to the Grammys to sing “Maggie’s Farm,” his voice was a croak, his face an eroded monument, his clothing antique. He gave off a vaudevillian vibe. He could have been teleported from the 1920s.

Even in person, Dylan left people baffled. He didn’t look like a cultural icon; he looked homeless. One day in 2009, a homeowner in Long Branch, New Jersey, called the police to report that an “eccentric-looking old man” had just wandered onto his property, which had a for-sale sign out front. A twenty-four-year-old beat cop reported to the scene and stopped the man for questioning. It was Dylan, and he told the officer that he was in the area to play a concert that night. But he didn’t look like the photographs she had seen of Dylan in his prime, and he was acting “very suspicious.” He was wearing two raincoats, the hoods up, and his sweatpants were tucked into his rain boots. She wondered if he’d walked out of the hospital. He also didn’t have identification with him, so she put him in the squad car and drove him to the hotel where he said his tour buses were parked. To her great surprise, the buses were there, and his people rustled up a passport and she let Bob Dylan go free.

Nina and the faithful saw what the world did not. They had placed an epic wager: Their man was not simply a songwriting giant, a performer par excellence and a figure of extraordinary literary merit. He was a man of lasting importance, unique in this epoch, an artist whose songs would be heard and discussed a hundred years from now. Future generations would laud them for their foresight. They got it.

When the world was bewildered by Dylan’s many costume changes—the angry protest singer (1962), the hung-up, lovesick troubadour (1964), the electrified composer of entire albums of surreal poetic masterpieces (1965–66), the missing rock star (1966–67), the rough-hewn sage from the dark woods (1967), the country singer with the sweet voice on “Lay, Lady, Lay” (1969), the heartbroken man from Blood on the Tracks (1975), the Christian convert (1979–81), the lost soul (1981–91), the traditionalist (1992–93), the man obsessed with the past (1997), the raunchy bluesman from Love and Theft (2001), the memoirist cribbing lines from ancient books, old magazines, and everything else (2004), the elder statesman worthy of an honorary Pulitzer Prize and a Presidential Medal of Freedom (2008–12)—they got it.

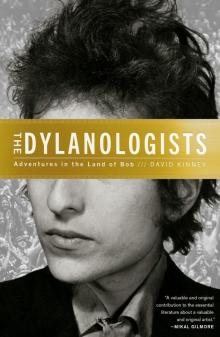

The Dylanologists

The Dylanologists