- Home

- David Kinney

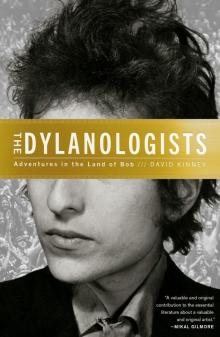

The Dylanologists Page 5

The Dylanologists Read online

Page 5

But the next year Peter’s father got a job working at Bell Labs and he uprooted the family. They ended up in the suburbs of north Jersey. Peter was back in public school, and it felt like he had been demoted. He hated it. He was a cog again. Rather than argue about issues of the day, students were expected to focus on straight schoolwork. Teachers lectured, kids listened. Peter did what any bored, intelligent kid would do in the 1960s. He grew his hair long and started looking for ways to show his contempt. He tucked a miniature American flag into the pocket of his sport jacket like a handkerchief and used it to wipe his face at lunch. (“That,” he said, “got the shit beat out of me.”) He wore a tiny yellow button reading IT SUCKS to school one day, earning him a visit to the school disciplinarian’s office. “What does this mean?” he asked. Peter tried to explain, but what could he say? When the man said he would be keeping the button, Peter refused to leave. He sat there for hours. Finally, his father was called. This impromptu sit-in concluded when the administrator agreed to mail the disputed button back to the Browns.

One day, hanging around the house, Peter decided to shout something at the world. He picked an unconventional canvas: the family lawn, which the Brown boys had allowed to grow as long as their hair. He sent a friend inside to an upstairs window. Outside, Peter fired up the lawn mower and started to form a message in giant letters, like his own twisted crop circle. His friend’s job was to shout directions so Peter could get it exactly right, and he did. When he finished, the Brown lawn in the respectable suburb of Millburn, New Jersey, read FUCK YOU. He thought it was just about the funniest thing. If anybody had asked him what exactly he hated about that town, he would have said, Everything.

His parents sent him to a therapist in East Orange. Peter and the man spoke a few times but they weren’t really getting anywhere. So Peter asked a friend if he could borrow his portable turntable. He set the player up in the therapist’s office, pulled Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home out of its cardboard jacket, and stuck the needle to the vinyl on side two, song three. He hoped the therapist would listen closely.

3

All through those early years, Dylan visited Guthrie in the hospital. His star was rising while his idol’s condition was deteriorating. Once, when Dylan was having a rough stretch, he stopped in hoping to have a real conversation. But as he tried, it struck him that it was hopeless. Whatever he had come all this way to find from Guthrie—inspiration, validation, the truth—this broken-down man could not provide. Dylan had gone to the hospital that day the way a supplicant goes to a priest. “But I couldn’t confess to him,” he said in an interview a few years later. “It was silly. I did go and talk with him, as much as he could talk, and the talking helped. But basically he wasn’t able to help me at all. I finally realized that.”

Dylan also realized in a hurry that he did not want to be pigeonholed as the new Guthrie. In the year and a half after he crashed into Gerde’s with “Blowin’” in his hands, that was a real possibility. Dylan wrote more than fifty songs during that stretch, good ones and so-so ones, sweet love songs (“Tomorrow Is a Long Time”) and bitter breakup songs (“Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”) and tender songs of heartache (“Boots of Spanish Leather”). But first impressions are hard to shake, and Dylan’s public image hardened like plaster. This was a writer of songs aimed squarely at the powers that be. “Masters of War” wished for the death of the men who build bombs. “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” conjured up Revelation with its numbered signs of apocalypse. “Oxford Town” contemplated segregationist mobs who fought a black man’s admission to Ole Miss. And then came “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” written after civil rights activists filled the National Mall for the March on Washington in 1963. Over a relentlessly pounding guitar, it captured America’s boiling political and cultural wars in five bristling verses. It drew battle lines.

Then everything did change, with President Kennedy’s shooting. Within a few months Dylan was telling interviewers that everybody had him wrong. He didn’t write “finger-pointing songs.” He wasn’t going to be the mascot for a social movement. Politics was a bunch of bullshit. The timing seemed curious. A few close friends told Dylan’s first biographer that he had been freaked out by the assassination. Would he be in the rifle’s crosshairs next? Around this time Dylan told a friend that prominent people who stood up and spoke the truth were doomed. “They’re going to be killed.” The change looked more sudden than it was. Dylan apparently had been growing more and more uneasy about the political bent of his work for some time, even as he wrote and performed fresh “topical” protest songs.

By 1964, Dylan began working to distance himself from the political agitators. But it was too late. The politically engaged songs he wrote in 1962 and 1963 were pitch-perfect for a radical new generation. Though Dylan could say he was no spokesman, he could not unsing the songs. Now they belonged to the dissidents—people under thirty, full of vigor, bursting with fresh ideas about how the world should and should not be. Dylan’s elusiveness only fed his reputation as a cult leader of the mutineers.

Folk purists were upset, but Peter was too young to be bothered. He mainlined The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and The Times They Are a-Changin’. He went to see Dylan in concert; the first time was in Newark eight days after the Kennedy assassination. Times gave him a line to end every argument with his parents: “Don’t criticize what you can’t understand.” He began devouring every article about Dylan and buying every new LP.

In early 1965, the new record was Bringing It All Back Home. It had Dylan’s absurdist sensibility stamped all over it. On the cover, Dylan was pictured on a chaise holding a gray cat in his hands, surrounded by blues records, a fallout-shelter sign, and an issue of Time magazine naming Lyndon B. Johnson its Man of the Year. On the back was a surreal poem in which Dylan is accosted at a parade by a middle-aged druggist running for office who accuses him of causing antiwar riots and vows that, if elected, he would have Dylan electrocuted publicly on the next Independence Day. The opener, “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” is a study in paranoia. He warns kids to watch out for cops and be wary of anybody holding himself up as a leader. “They keep it all hid!” The songs howled that the world was twisted and corrupt, unfixable by politics or any other tool at the hand of man. For all the talk of Dylan shaking off the mantle of generational spokesman, Peter heard a singer taking protest to sweeping heights.

This was the album Peter brought into his therapist’s office. The track he played was “It’s All Right, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” Dylan at his scorched-earth finest. “Money doesn’t talk, it swears,” he spits. The world is filled with phonies, and nothing is sacred. The authorities would execute him if they knew what he was really thinking.

“This is how I feel,” Peter told the shrink. “Everything that I’m trying to tell you is on this record. It’s all there.”

The therapy sessions ended. Peter kept buying Dylan records.

In 1965, Peter attended a summer camp near Poughkeepsie founded by Jewish socialists. Camp Kinderland got teens thinking about social justice, peace, and equality. In 1958, Dylan’s future New York City girlfriend, Suze Rotolo, had been a counselor at the camp; by the time Peter arrived, Dylan was spoken of like a minor deity. In between swimming and hiking and plays, the kids sang Yiddish labor songs. They didn’t wage color wars, but instead competed in the Peace Olympics, during which teams prepared presentations on far-off nations. In months and years to come, every Vietnam War protest Peter attended felt like a camp reunion. They would take the train down to Washington singing folk songs.

Camp broke up that year the day Dylan was scheduled to play a tennis arena in Queens. Half the campers had tickets. Peter jumped off the bus at Union Square, dumped his duffel of dirty clothes on his dad, and bummed around the city for a while with some other Dylanheads before heading out to Forest Hills. It was a cloudy day, raw for August. They were excited: They knew this was going to be differe

nt from any Dylan show they had seen before. Standing in line, they heard a full band, electric and amplified, doing a sound check.

One month earlier, Dylan had appeared at a music festival in Newport, Rhode Island, held at a city park that had hosted open-air vaudeville shows at the turn of the century. The festival, three days of workshops and concerts first staged in 1959, had evolved into the most important event on the folk calendar. Dylan went on with a full electric band. This was not what traditionalists expected from their young hero. He had already stopped writing protest songs. Now he was pairing his lyrics with rock music? This was not a mere question of aesthetics. Folk was music of the people, created and handed down anonymously over generations. It aspired to a return to simpler times and values. Rock was juvenile, temporary, and, worst of all, commercial. Dylan was supposed to be a nonconformist, outside the mainstream, bucking the system. That’s why his admirers loved him so. That’s what had given him such power.

He wore a black leather coat—“a sell-out jacket,” one observer called it—and carried a sunburst electric guitar. In a set that began and ended in a few short minutes, a brief summer squall, Dylan proceeded to cause a controversy of such epic proportions that nobody could agree exactly what happened. It passed into mythology so quickly that nobody had time to nail down the facts. If you believed the most incendiary accounts, Dylan caused a near riot. Men fought around the soundboard. The great Pete Seeger was so angry he threatened to chop the power lines with an ax. The crowd booed Dylan from the stage. He left in tears. By all accounts, some people did jeer Dylan, but it was unclear why. Were they upset by the electric band, or by the poor sound quality that made Dylan impossible to understand, or by the brevity of the performance? No one could say for sure. What’s interesting is that if you listen to the recording, you will hear, of all things, cheering. Raucous, enthusiastic cheering. “I don’t hear any fuckin’ boos,” Peter says. “Where they booed was Forest Hills. That’s where they fucking booed. I was there, and they booed.”

Word about Newport had filtered down through folk circles, and Dylan’s rocking “Like a Rolling Stone” was in heavy rotation on the radio. So as Peter and the other kids packed onto the benches in the concrete stands at Forest Hills, they had a sense of the spectacle they were about to witness. They were euphoric but surly. The atmosphere was tense. The courts, broad expanses of perfectly manicured grass, separated the kids from the stage. Cops stood watch.

As showtime approached, cold gusts whipped around the arena. A reviled disc jockey from commercial radio gave an introduction during which he appealed to the kids to keep an open mind about Dylan’s new sound. “I would like to say this: There’s a new, swingin’ mood in this country, and I think Bob Dylan perhaps is the spearhead of that new mood. It’s a new kind of expression, a new kind of telling it like it is, and”—here he slipped in a plug for the pop music special he had hosted on television earlier in the summer—“Mr. Dylan is definitely what’s happening, baby.”

The kids in the audience booed with glee.

A spotlight followed Dylan onto the stage. He came on alone with his guitar and harmonicas. The wind whipped his hair. He played a long new song, one the audience had not heard before. Cinderella looks like she might be “easy” as she slips her hands into her back pockets. Ophelia wears an iron vest. Einstein dresses as Robin Hood. The fans didn’t catch all of “Desolation Row,” but they loved what they could make out. They laughed and laughed at the hip reinventions of characters they knew from school. This was their man.

Then, intermission. Backstage, Dylan told the band to stay cool. Anything might happen. Just keep playing.

The band came on and the crowd made noises that, to music critic Greil Marcus, sounded like “someone being torn to pieces.” A Village Voice correspondent described a riotous throng split evenly between nascent rock fans, who cheered, and folk purists, who chanted, “We want Dylan!” “The factionalism within the teenage sub-culture,” he wrote, “seemed as fierce as that between Social Democrats and Stalinists.”

“Scumbag!” somebody screamed between songs.

“Aw, come on now,” Dylan said.

Peter watched it all in astonishment. “It was insane!” Kids jumped the barricades and scrambled across the tennis court and up onto the stage, with guards stumbling in pursuit. It was hard to tell whether the fans had foul designs or just wanted to dance. They scurried around, ducking security. Later, the musicians said they were scared because they couldn’t make out what was happening in the crowd. In the stands, Peter thought there was a real chance of violence.

But the show ended and the masses streamed toward their homes unscathed. Peter hadn’t joined in the chorus of discontent. It would have been perfectly understandable if he had thrown in with the traditionalists who felt betrayed by this commercial sound. He loved the folk music he’d grown up hearing. He was upset when he first learned that Dylan was going electric. But the sinking feeling only lasted for a couple of days. He was only fourteen; he couldn’t be permanently disillusioned.

What changed his mind were the songs. Listening closely, he could tell it was the same man he had been obsessed with for the past two years. If the words were still uncompromisingly Dylan, what was the problem?

That night in Forest Hills, Dylan dashed backstage and into a station wagon. He sped back to his manager’s apartment in Manhattan for an after-party, where he got to talking with a woman who had seen the concert. How did she like it? She demurred. When he pushed, she admitted she didn’t much like the new songs. He asked if she’d booed. No, no, nothing like that, she replied. To which Dylan said, Why not? If you didn’t like it, you should’ve booed.

Some days later an interviewer asked what he thought of the catcallers in Queens. “I thought it was great,” he said. “I really did. If I said anything else I’d be a liar.” He loved the confrontations and he wasn’t backing down. He had found a way to make the music he wanted to make, and it would take more than jeers for him to go back to what he had been doing before he rolled into Newport. “They can boo till the end of time,” he added. “I know that music is real, more real than the boos.”

4

He had been asked to explain himself before, and he’d tried. A year earlier, he had sat for an interview with writer Nat Hentoff, and the resulting piece in the New Yorker elegantly captured Dylan in his early twenties. He was no one-dimensional Guthrie clone, but a young man who was still growing, and evolving, “restless, insatiably hungry for experience, idealistic, but skeptical of neatly defined causes.”

The magazine gave Dylan the space to voice, at length, his idiosyncratic view of the world. Hentoff asked why he stopped writing “finger-pointing songs,” as Dylan called them, and instead had recorded an album almost entirely about women and love and relationships. “I looked around and saw all these people point fingers at the bomb,” he explained. “But the bomb is getting boring, because what’s wrong goes much deeper than the bomb. What’s wrong is how few people are free. Most people walking around are tied down to something that doesn’t let them really speak, so they just add their confusion to the mess. I mean, they have some kind of vested interest in the way things are now.” There could be no change because people—individuals—were too concerned with their own status.

Dylan said he held the same views on civil rights as the youthful activists, but he couldn’t bring himself to join in their work, go south, and carry a picket sign or something like that. “I’m not a part of no Movement. If I was, I wouldn’t be able to do anything else but be in ‘the Movement.’ I just can’t have people sit around and make rules for me. I do a lot of things no Movement would allow. I just can’t make it with any organization.”

He said a lot in this vein, to Hentoff and a few other sympathetic writers. But the mainstream press didn’t catch on. He was moving too fast. And anyway, these were not the sorts of ideas reporters on deadline could fit into a tidy, unco

mplicated newsprint narrative. He thought about the world in fundamentally different ways. He rejected what others took as given. He quickly grew tired of answering questions from reporters who were uninformed by anything more than the media echo chamber, the tabloid journalists and radio hosts who wanted to ask him about folk music and protest songs and how it felt to be the spokesman for the generation. He had moved on.

He upended journalists’ assumptions and turned their questions inside out. He dismissed them as a bunch of “hung-up writers” and “frustrated novelists.” He lashed out with humor, anger, sarcasm, and silliness while his entourage of knowing hipsters hooted on the sidelines. “Why should you want to know about me?” he asked one helpless journalist in England. “I don’t want to know about you.” He got writers to agree to spoof interviews. Hentoff did one for Playboy in 1966. It got to be hard, after a while, to tell what was real and what was not, which was exactly how Dylan wanted it.

In December 1965, four months after Forest Hills, he reacted incredulously to questions at a press conference to promote a pair of concerts in the Los Angeles area.

“I wonder if you could tell me,” one questioner asked, “among folksingers, how many could be characterized as protest singers today?”

“I think there’s about a hundred and thirty-six,” Dylan deadpanned. “It’s either a hundred and thirty-six or a hundred and forty-two.”

“What does the word protest mean to you?”

“It means singing when you really don’t want to sing,” he said.

“What are you trying to say in your music? I don’t understand one of the songs.”

The Dylanologists

The Dylanologists